Amitesh Kumar has one of the toughest jobs in Mumbai. From his sixth-floor office overlooking the sea at Worli, Kumar has to ensure traffic moves smoothly in one of the world’s most populous cities. That is easier said than done, given that India’s financial capital is notorious for its interminable gridlocks. During our 30 minute conversation, the bespectacled joint commissioner of police (traffic) had to stop mid-sentence several times to attend to calls and visits by officials. To the right of his desk is a nearly wall-sized screen with 16 windows showing live feeds from CCTVs — there are 5,217 in all installed on various roads of the city.

Talking in a measured tone, Kumar is quick to rattle off statistics: there were 41,000 speeding violations in the city in 2017, which shot up 19 times to 7,70,000 in 2018. What changed? In January 2018, the Mumbai traffic police started installing cameras with automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) system.

These cameras — there are 56 in the city — are more effective in zeroing in on speeding motorists than portable speed guns.

Use of such technologies, combined with the identification of accident-prone spots and a crackdown on drunk driving, has brought down Mumbai’s road fatalities 15% from a year earlier to 430 in 2018, says Kumar. “Enforcement should be strict enough to act as a deterrent.” ANPR cameras have also been installed in other parts of the country, including the NCR, Hyderabad and Kolkata.

With safety increasingly become a top priority for authorities, it would not be wrong to say that our roads are becoming less dangerous, according to some metrics such as the number of accidents, though fatalities are still a problem. Quality of roads, which has a huge impact on safety, has seen a marked improvement over the years. But quality and safety are still very much works in progress and India cannot afford to take its eyes off the road.

An indicator of improving quality of our roads is the increasing number of lanes separated by a median, which avert head-on collisions, says Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman and cofounder of integrated infrastructure services provider Feedback Infra.

Piyush Tewari, founder of non-profit SaveLife Foundation, says steps like plugging gaps in medians, which prevent illegal U-turns, also help. SaveLife worked with the Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation to identify engineering factors responsible for crashes on the Mumbai-Pune expressway. They identified median gaps, missing shoulders (on the side of the road) and plants obstructing vision, among others. In 2016, when the NGO started working on the project, there were 151 deaths on the stretch. In 2018, the figure fell to 110, says Tewari.

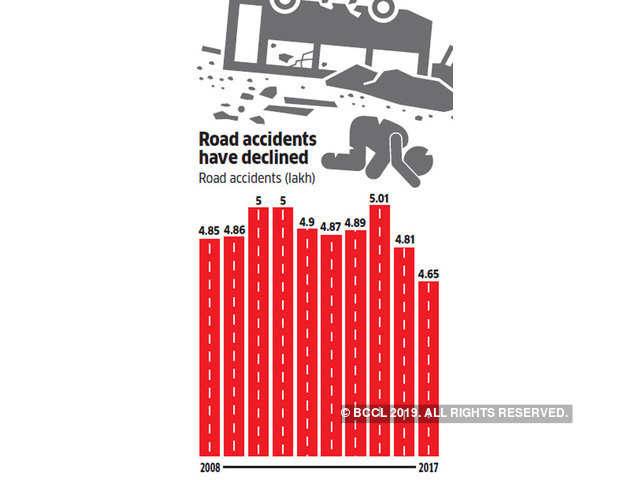

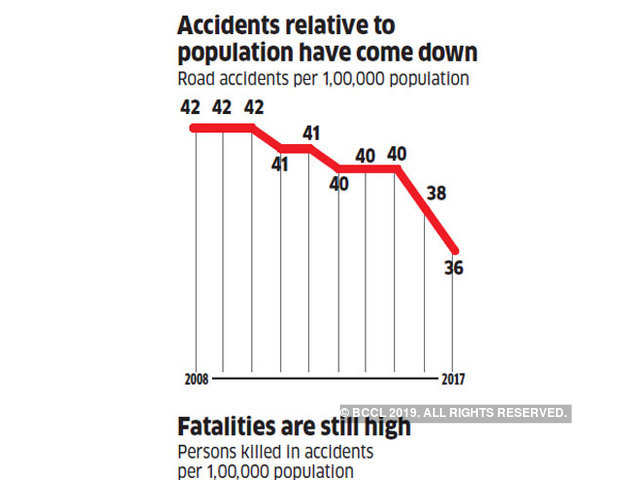

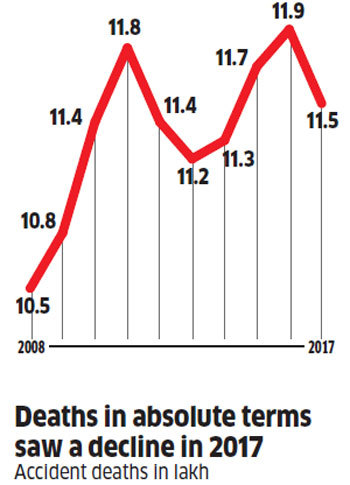

Road accidents in India have declined from 42 per 1,00,000 population in 2010 to 36 in 2017, according to the ministry of road transport and highways. Even in absolute terms, road accidents have been falling since 2015, and the 2017 figure — 4,64,910, or 53 every hour — is the lowest since 2006. But it is a slightly different story in fatalities due to road accidents. While both absolute deaths and fatalities per 1,00,000 population declined marginally in 2017 — to 1,47,913 (17 every hour) and 11.5, respectively — the number of fatalities per 100 accidents rose from 31.4 in 2016 to 31.8 in 2017.

Interview requests sent to Nitin Gadkari, minister for road transport, did not yield any response.

One explanation for the high level of fatalities is the woeful state of emergency response across the country. There are over 25,000 ambulances plying under the National Health Mission. Of that, around 9,300 ambulances are for emergency response through the tollfree number 108. Besides, hospitals and private companies also operate ambulances.

But there is no data available on how many road accident victims lose their lives because of lack of medical attention within the first hour of the mishap, called the “golden hour” when treatment can mostly prevent death.

India has the highest number of road fatalities in the world. In 2016, the latest year for which global figures are available, India accounted for more than a third of global road accident deaths. The World Health Organization says such deaths are under-reported and estimated that in 2016, the figure for India was likely twice as big as that reported by the government.

Even the Indian government’s figure is alarmingly high. But technologies like ANPR cameras and other safety interventions will start giving improved statistics in a few years, says S Sundar, a former Union transport secretary and a fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute.

India, despite having around 230 million registered vehicles, does not have a national road safety policy. The only legislation to deal with road safety is the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988. An amendment was proposed to the law to ensure children’s safety while commuting, increase penalties in line with inflation, ensure liability of road contractors, digitise the licensing system and to recall old vehicles that do not adhere to safety norms. It was passed in the Lok Sabha in 2017, but faced opposition in the Rajya Sabha, particularly from regional parties, supposedly over state governments’ powers being taken away. The ordinance has now lapsed. India is a signatory to the 2015 United Nations Brasilia declaration, which aims to cut road traffic deaths and injuries by half by 2020.

One reason for bad driving habits is that most people do not go through formal driving lessons before getting a licence, says Tewari of SaveLife Foundation. “And in several places you can get your licence delivered to your home for a price.” Improving driving skills and a proper licensing system can ensure better road behaviour and effective law enforcement.

Getting riders to wear helmets and those travelling by car to wear seat belts, simple as they may seem, has proved to be challenging. But these can help reduce fatalities. Enforcement without the physical presence of personnel, like ANPRs, is fast becoming the norm around the world. “Cameras don’t go home at night nor can they be bribed,” says Tewari.

But such methods are not without their lacunae. For instance, less than half the offenders identified by ANPR cameras in Mumbai actually pay the fines. In an ideal situation, a text message would go to the offender with a link to an e-challan, along with a picture of him taken by the camera. But if the motorist’s mobile number is not linked to his vehicle documentation, it does not work. The driver finds out about past penalties only when he is stopped by a traffic cop for a different violation and his vehicle number is run through the database, or if the driver does the check himself.

That is what happened to Mayank Singh in 2018. He had bought a Renault Duster in December 2017 and used it to drive from Mumbai to Pune. In March 2018, he learned that he could go to www.mahatrafficechallan.gov.in and find out if he had violated road rules. He found out that he had exceeded the 80 km per hour speed limit 17 times in Mumbai and had racked up penalties of `17,000. “After that, I became speed-conscious at those points and used to check online every fortnight.” In September, he relocated to Jakarta for work.

The fundamental problem with our roads is they are designed for motorists. “Pedestrians are not prioritised and that should change,” says Kelly Larson, who oversees Bloomberg Philanthropies’ work on road safety in 10 cities across the world. Pedestrians accounted for 13% of those killed in accidents in 2017 in India.

Not far from Joint Commissioner Amitesh Kumar’s office, Girija Ambala had to pay with her life due to the carelessness of another person. A speeding motorcycle with three young men hit Ambala when she was crossing a road on a January evening in 2018. Her jacket snagged on the handlebar and she was dragged for 100 meters. She sustained fatal injuries to her skull. Ambala was to turn 20 three weeks later. Her father, Ganga Murli Ambala, says pedestrians had complained about speeding on this stretch of the road for years but no action was taken.

Not much has changed since the tragedy, he adds. “They can’t put cameras everywhere but they should at least have speed breakers every 50 or 100 metres and a zebra crossing. That way, it is very hard to speed.” The straighter a road, the lower the chances of an accident on it. But a linear stretch is not always possible because of the terrain and land acquisition problems.

Road Index

Aside from factoring safety considerations into the design of a road, the quality of Indian roads has seen a notable improvement over the past decade or so. For instance, an annual survey of business executives conducted by the World Economic Forum on the quality of roads in around 140 countries reflected that.

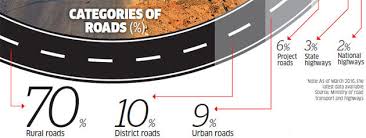

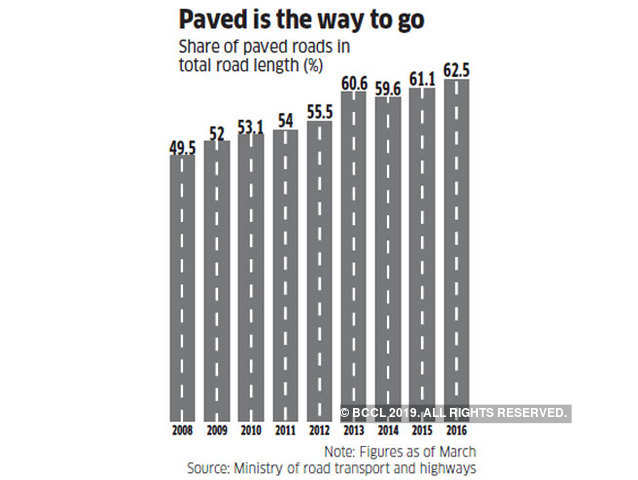

Between 2008 and 2018, India’s rank in road quality rose from 87 to 51. The share of paved roads in our road network has increased from half in March 2008 to nearly two-thirds in March 2016, according to the latest available figures. India has a road network of 5.6 million km, of which national highways contribute just 2% and state highways 3%. Rural roads account for the lion’s share, at 70%.

While national and state highways almost entirely have a black top surface (with bitumen as a binder) or cement concrete, just over half of rural roads are paved.

National highways, which carry 40% of the country’s road traffic, get most of the attention among roads and have been one of the few bright spots in infrastructure development over the past few years; 34,300 km were built between April 2014 and November 2018. “Earlier, there were mostly brownfield projects, which were for the widening of highways and there were latent defects in the design we had to work with. But now there are a lot of greenfield projects,” says Satish Parakh, managing director of Ashoka Buildcon, which has built 10,000 lane-km of roads so far. Lane-km takes into account the number of lanes constructed on a km. So 4 lane-km would mean four lanes of one km each have been constructed. Besides highways, rural roads have also seen a transformation, especially under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana. Launched in 2000, this scheme has led to the laying of around 5,80,500 km of rural roads.

But all is not rosy. Reports of worsening potholes after rains are common in cities, due to inefficient drainage, and multi-lane highways are built without into account the needs of villagers who need to cross it, resulting in accidents. Most of India’s roads do not befit the fastest-growing major economy and way too many people lose their lives in accidents. But there are certainly signs of change.

Date: November 11, 2019

Leave a Reply