Motorists have not welcomed these changes. Many have refused to comply and, in one extreme instance, even burnt their vehicle in protest. Though several states are already diluting these amendments (since it falls under the concurrent list), the central government believes these are necessary changes to improve India’s road safety. Data and research, though, suggests that this may require more than just heftier penalties.

Of all the new policies implemented by the Modi 2.0 government, few have affected Indians in almost every part of the country as much as the new road rules. The Motor Vehicle (Amendment) Act, passed in August 2019, made significant changes to how India’s roads are governed. Road construction standards were changed, insurance norms tweaked, and most controversially, fines for traffic violations were hiked.

Motorists have not welcomed these changes. Many have refused to comply and, in one extreme instance, even burnt their vehicle in protest. Though several states are already diluting these amendments (since it falls under the concurrent list), the central government believes these are necessary changes to improve India’s road safety. Data and research, though, suggests that this may require more than just heftier penalties.

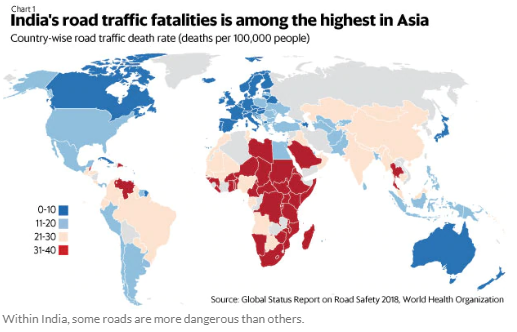

In his defence of the motor vehicle amendments, Nitin Gadkari, the roads minister, suggested that India’s deaths from road accidents are the highest in the world. The latest global report on road safety from the World Health Organization, however, suggests that India fares poorly but is not the worst. In 2016, India’s death rate (fatalities from road accidents per 100,000 people) was 22.7, the 58th highest death rate out of 175 countries and higher than both Pakistan (14.3) and Bangladesh (15.3).

Broadly, road safety seems to be correlated with a country’s wealth: richer countries tend to have safer roads. For instance, the top ten countries with the fewest road deaths include Singapore, Sweden and Norway while countries with the worst records are largely poorer countries from sub-Saharan Africa. As part of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, many of these countries have committed to halving the number of injuries and deaths from road accidents by 2020 (compared to 2015 levels).

The brunt of the damage is borne by the young: globally, 15-29 year-olds are most likely to lose their lives to road traffic accidents. These tragic losses also have significant economic costs. One World Bank report estimates that halving India’s accident rate between 2014- 2038 could generate an additional national income flow worth 14 percent of GDP over the period.

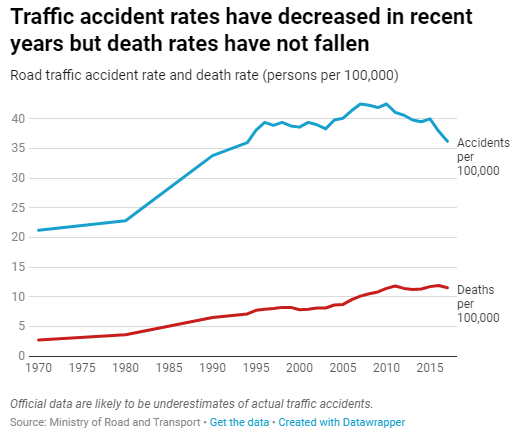

India, however, is a long way from meeting this target. According to the latest data from the road transport ministry, there were 464,910 road accidents in India in 2017 which resulted in 147,913 deaths (or 11.5/100,000 people). These figures are also likely to be underestimates. Many accident cases, especially in rural areas, go unreported which could mean that accident fatalities are actually 47 percent -63 percent higher than official data, according to the Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme (TRIPP) at IIT Delhi.

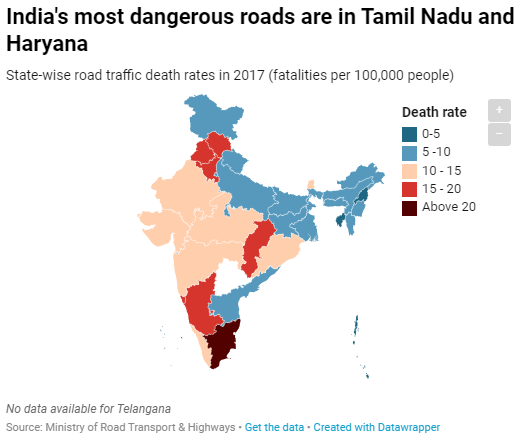

Within India, some roads are more dangerous than others. Among India’s larger states (with populations greater than 10 million), the most fatal roads in India are in Tamil Nadu (death rate of 23.2) and Haryana (18.4) while the safest roads are in Bihar (5.3) and West Bengal (6.1). These differences are a result of varying patterns of vehicle ownership, road infrastructure and rule enforcement across states, according to TRIPP.

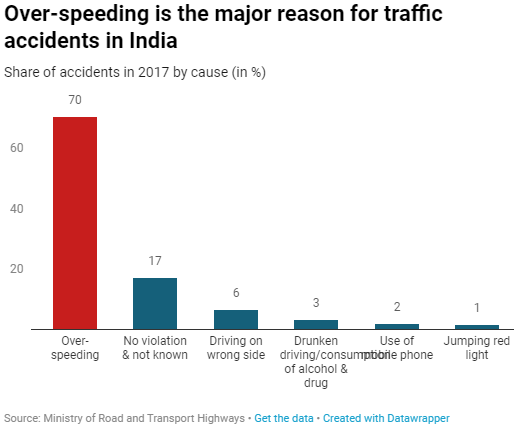

In most states, the biggest reason for road-related fatalities accidents is road-speeding with 70 percent of all accidents and 67 percent of traffic deaths in 2017 attributed to drivers breaching speed limits. According to WHO, every 1 percent increase in mean speed generates a 4 percent increase in the fatal crash risk. Tackling this is a priority for any government and explains why the current government has hiked up fines for speeding from Rs 500 to Rs 5,000.

In theory, heftier fines should act as a deterrent for speeding but in practice, this may not happen. Higher fines could mean more rent-seeking as drivers pay off authorities to avoid fines or simply abscond. According to TRIPP, the global experience with imposing stricter penalties has not proven to change driver behaviour and has even decreased overall enforcement of penalties. A better strategy, then, could be to ensure that speed limits are enforced more regularly. The WHO’s global report, which measured enforcement levels across the world, rated India’s enforcement as fairly weak. One way to address this could be through technology such as speed cameras and in-vehicle sensors.

However, better enforcement alone may not be enough. The United Nations’ prescription for road safety policy is that it should focus on five key areas together: improving road safety management capacity; developing safe infrastructure; rolling out safer cars; changing road-user behaviour and improving post-crash care.

Date: September 23, 2019

Leave a Reply